Landrace Thai Strains & Southeastern Asian Cannabis

You’ve probably heard about Thai weed or landrace Thai strains, but if you’re like us, you’ve heard a lot of different things that can’t all be true. We dug through a multitude of resources to help piece together some of the culture and history of cannabis in Thailand and Southeast Asia.

We’ll start with Thai Stick, move into history and smuggling, try to get a finger on what Thai weed was really like, and, lastly, suggest some ways to track down the real deal in today’s market. Let’s get into it!

Myths about Thai landrace cannabis: Thai Stick

One of the favorite topics for old-timers and vintage enthusiasts are the famed Thai Sticks. But what the hell is a Thai Stick? Some say it’s a rare strain that went extinct, some say it's a rolled-up cigar, and others say it’s weed dipped in opium. Turns out, it’s none of the above.

Over the years, Drug War propaganda has mixed with tall tales from our youth, and the result is a continuous cycle of misunderstandings about landrace strains and traditional cannabis culture. That couldn’t be more true with the legendary Thai Stick. Most of the information returned by Google about Thai Stick is inaccurate, including articles from High Times and other reputable publications. So, what does ‘Thai Stick’ really mean?

What is a Thai Stick? Is Thai Stick a cigar?

The term Thai Stick refers to a packaging method that is common in parts of Southeast Asia. When bringing goods to market, they are often tied to a stick for transport and bundling. It’s an easy way to portion goods without a scale, similar to the way vegetables at an American farmers market are bundled with rubber bands. It’s important to note that Thai sticks are just containers, not smokable cigars. Instead of pulling buds out of a bag to break them down and smoke them, you pull a bud off of the stick.

As far as smoking the Thai Stick like a cigar, it may be possible to pull out the stick and wrap it in a paper, but traditional Thai Sticks never came pre-wrapped due to the risk of mold.

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

Is Thai Stick also a strain?

Another point of confusion is that Thai Stick refers to a particular landrace strain or cultivar group, but again, it only refers to the stick that buds are wrapped around, not the type of weed. The ‘tropical sativas’ imported from Thailand during the ‘70s and ‘80s would have been distinct to American consumers, but included many different varieties. In that sense, the Thai Stick that made it to the United States would be very unique, but in those days, strains weren’t labeled like they are today, and names like “Acapulco Gold” referred more to everything that came from a certain region rather than one specific strain.

In the 1970s, the classic Thai Stick would have come in several varieties from many different farmers, but it was generally expected to have a strong and long-lasting ‘pure sativa’ effect. As time went on, imported Thai Stick was hybridized and grown on larger and larger farms that produced less variety than the small farmers who originally supplied American smugglers.

Was Thai Stick dipped in or sprinkled with opium?

No. It probably happened from time to time, but it never happened on a large scale for several reasons. For one, the wholesalers for marijuana and opium were not the same people, and their crops grew in completely different parts of Thailand and the surrounding region. Two, it just doesn’t make sense economically. Opium was much more expensive and the cost of Thai Stick in the United States was already many, many, many times higher than competing products. Third, it’s a logistical problem. Lacing marijuana with dry opium would be tricky and wasteful, while dipping buds in an opium solution is risking total crop loss due to mold or mildew growth.

There’s probably two reasons this myth is so pervasive. The first being that Thai weed was (and still is) really, really strong. Due to various environmental conditions, it’s practically impossible to grow weed that’s as sticky in the United States, with the exception of Hawaii. We’re talking coated in resin, enough that it will literally stick to the wall and stay there. On top of that, most of the cannabis in the United States comes from hash plant strains which weren’t selected for smoking flowers, whereas Southeast Asian farmers selected for potency and effects without making hash first.

The second reason has more to do with the War on Drugs and propagating fear, which is still common today. We are constantly bombarded by myths about weed laced with fentanyl. Before that it was PCP, and even earlier it was opium. Very few examples of these products actually exist, but that doesn’t stop headlines from stirring things up, and so the cycle continues.

What does Thai Stick look like? How big was a Thai Stick?

In an interview with the Future Cannabis Project, smuggler Mike Ritter breaks it down, saying, “A typical Thai Stick was about five and half inches long, it was a piece of bamboo. Later on they made them short, this and that, but that was a typical Thai stick. Those were bundled together in units of twenty, and that was a bundle, twenty Thai sticks, and then those were put in a bag of a hundred bundles … that weighed about three and half kilos.” That big bag of bundles was called a toom.

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

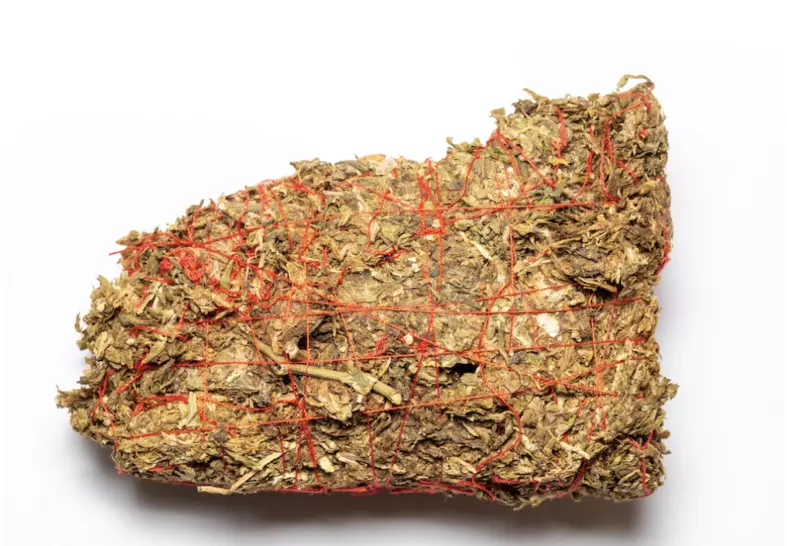

As time went on and smuggling operations scaled into sophisticated operations, these bundles were pressed for packaging in a way that resembled ‘brick’ weed more familiar to most Americans. This was usually still called “Thai Stick” even though it was no longer tied to a stick.

How much did Thai Stick cost? Do Thai Sticks still exist?

It’s hard to believe, but in the 1970s, good Thai Stick went for $2000+ a pound. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $10,000 a pound! At the time, Acapulco Gold, Panama Red, and Columbian Gold would have sold for around $200 a pound ($1,000 in today’s dollars). Even though the highest-end exotics on today’s market can fetch up to $10,000 a pound, that’s not the tenfold increase over competing products that Thai Stick sold for.

Adjusted for inflation, an eighth of premium Thai Stick could have gone for $350, which means it was a highly exclusive product reserved for wealthy Americans. So while Thai Stick certainly doesn’t have the look that appeals to the modern high-end market, it has effects that can’t be easily replicated, and in those days, nothing was more exotic than that. Whether or not those legendary products will ever return to market is hard to say.

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

Courtesy of Peter Maguire @thaistickbook

The history of weed in Southeast Asia and Thailand

One of the first things to realize when exploring Thai landrace strains is that ‘Thai’ weed isn’t necessarily from Thailand per se; that’s just where Westerners have had the most access to cannabis markets and wholesale dealers over the years. Throughout the ‘70s, much of it may have been grown in Thailand, but modern ‘Thai’ weed is more likely to come from Laos, and possibly Cambodia or Burma. In this sense, it might be better to think of ‘Thai’ landrace weed as a group of Southeast Asian varieties which have seen shifts in regional production due to changing political conditions.

The mountainous regions of the Yunnan Province in China may have yielded some of the first domesticated hemp between six and 12 thousand years ago, which was later brought into the surrounding regions, including Laos, some 2,500 years back. Although this aromatic flowering hemp can still be found there, it’s low in THC and distinctly different from the drug-type cannabis that's often remembered as Thai Stick. The first evidence of recreational cannabis use dates back to around the same time, but is attributed to the Scythian people, a nomadic tribe from modern-day Iran. It’s certainly possible that the Sycthians got their weed from somewhere near Thailand where it would have evolved from hemp, but evidence points towards the Hindu Kush mountains as being a distinct point of origin for drug type cannabis. In that case, the Sycthians may have brought it to Southeast Asia some thousands of years ago.

Lao cannabis culture in Southeast Asia

How and when drug-type cannabis arrived in Southeast Asia in the first place is not totally clear, but over the last several hundred years, Lao people have a history of breeding and flower production that may be the first historical example of smokable ‘sinsemilla’. Despite widespread cultivation across the region prior to the War on Drugs, it's suggested that even landrace strains grown in Thailand today are often bred by Lao farmers. That’s not to say that Thai people don’t have a long history of using medicinal and recreational cannabis, though. According to Thai Stick author Peter Maguire, before the 1970s, it was often referred to by Thais as “Chinese aspirin” and could be found growing in most people’s yards. Maguire also mentions that Thai farmers would feed it to their pigs to increase their appetites! At the time, it was primarily used by older folks and had very little appeal to younger Thais.

With the eradication efforts and increasing penalties spurred by the War on Drugs, the production of the household medicinal plant receded into nearby mountains and more secluded areas of the region, where its distribution fell into a network of farmers and brokers who used money, political connections, and other means that kept them safe from legal consequences and the many pitfalls of smuggling contraband.

American smuggling in the Drug War era

There are two substantial reasons that ‘Thai’ weed is so prolific and well-known in the United States. One is that the Vietnam war allowed for the development of American commercial ventures and tourism in the region that eventually spilled over into clandestine partnerships between Western smugglers and local cannabis farmers. The other, explored below, was already mentioned — Laotian farmers have a history of quality flower production. But first, the smuggling.

Depending on your age, imported Thai buds may have at one time been a familiar product to you, but it’s virtually disappeared from the American market. That doesn’t mean it’s not around, but these days, ‘brick’ weed would be an unthinkable purchase for most American consumers. Americans who didn’t smoke until the 1990s or later tend to associate smuggled weed with Mexican ‘brick’, which generally isn’t a fond memory compared to the growing market of west coast outdoor and hydroponic products like Northern Lights.

Before indoor growing technology shook up the scene, buying weed in the U.S. was a seasonal affair. Peter Maguire (the author of Thai Stick) said in a Future Cannabis Project interview, “Back then in California it was ‘purple seedless’, which is what we used to call indica in the winter, and then it was Thai in the late spring, early summer, and throughout the summer.”

Maguire went on to outline the often overlooked role of surfers like Mike Ritter in the early days of the Thai marijuana trade. Describing his first hash oil smuggling trip to Bali with two hollowed-out surfboards, Ritter says, “At that time, I was taking a pound, maybe two pounds, something like that. That’s what everybody was taking, just a little bit of profit to keep your surfing venture going.” From there, Ritter wound up being hired in Singapore to fabricate fiberglass suitcases with hidden compartments, which he took to Afghanistan. The gigs paid off, but didn’t last. In 1972, a coup in Afghanistan shut the doors on his first smuggling routes but, Ritter says, “At the same time, this promising new source of cannabis, Thailand, appeared.”

The changing landscape of Prohibition

After running surfboards, suitcases, and vests for a while, Ritter says, “Pretty soon it worked up to where boats were the thing to do … I became a broker.” A captain with a smuggling boat would come to him in Thailand, where Ritter coordinated everything on the supply side, first requesting loads from Thai brokers who knew the mountain landscape and its farmers. After arranging meet-up locations up to 300 miles from the coast, he’d bring the loads out on Thai boats and, once delivered to the purchasing vessel, his job was done.

For smugglers like Ritter, this continued in much the same way for over a decade. Then, in the 1980s, redoubled efforts in the War on Drugs brought significant changes. Although DEA efforts focused mainly on Florida landing spots for Colombian imports, many smugglers of those routes looked for new ventures in less scrutinized places. When smugglers from Colombian routes showed up in Thailand, they were used to running BIG loads — up to 100,000 pounds at a time. According to Ritter, “Eventually it closed the whole Thai farming industry down altogether and the farming moved to Laos, and then the loads [were] grown in Laos and delivered out of Vietnam.”

This new wave of smugglers operated on a paramilitary level that involved heavily armed outfits of mercenaries and politically connected operations that further consolidated the trade of Thai marijuana into the hands of people with sophisticated commercial infrastructure. To emphasize this point, Peter Maguire told the Future Cannabis Project about one of the last major busts that would mark an end to Thai imports coming into the United States: “One of the last big loads… is on a ship called the Encounter Bay, and so the load is grown by these twin Green Beret brothers in Laos, it’s driven in Russian trucks to Da Nang, Vietnam, the Vietnamese Navy takes it out to their mothership, and so, you know, we’re seeing real globalism.”

Why was Thai Stick weed so strong? How is Thai landrace weed produced?

In addition to the commercial relationships resulting from the Vietnam War, Thai weed holds a place in American history for a completely different reason. It’s just good stuff! More specifically, it’s bred and selected for quality flower production which makes it much more similar to modern strains than most other ‘landrace’ products.

Southeast Asia has one of the longest cultural associations with quality seed production for flower production (whereas other parts of Asia are known for their hash). In the words of Angus, proprietor of The Real Seed Company and Kwik Seeds, Asia is fascinating because “It’s the biodiversity from the point of view of the plant itself that’s most interesting, and culturally it’s most interesting in terms of these long traditions of use, these counter-cultural traditions of use.”

In many ways, this cannabis culture that Angus mentions is most similar to the modern scene, whereas cannabis from other regions was either open pollinated or bred for hash production. Even today, Angus describes why Southeast Asian cannabis is so appealing to the modern market, saying, “In Thailand and Laos you have a farmer who's tasked with just producing seeds. So his job would be to grow a crop and make sure there’s no hermaphroditic plants in it and to do some selection with the potency”.

In Angus’s opinion, all of the modern hybrids that are considered high-quality smoke have lineage from ‘Thai’ genetics that were carefully selected in this way. In contrast, the Afghani strains that have been used to make those sorts of plants easier to grow don’t have that history of selection for quality bud because all of it is traditionally made into hash anyway.

What is Thai weed like? Smell, flavor, effects, and genetics?

Landrace Thai strains are best known for two fairly distinct sets of aromas. Some have a very floral scent that we associate with terpenes like terpinolene. These plants often exhibit citrus aromas and may have herbal notes, particularly of mint and even menthol. The other set of Thai landrace strains have a rich chocolatey, coffee-like complexity that takes on an overall earthy overtone.

Thai landrace strains are generally considered pure sativas, which they tend to be when it comes to their growth characteristics and structure. That doesn’t necessarily mean what people think, however. Many landrace Thai strains are tall, lanky plants with airy buds that still produce intensely narcotic and sedative highs. One example of this is the legendary Chocolate Thai, which is known for its relaxing and dreamy effects that are strong enough to knock a person into their seat or put them to sleep. Compared to modern hybrids, these strains are still fairly cerebral but not in the uplifting sense of the floral, herbal, and citrus varieties.

That’s not to say that Thai strains will always be one or the other and have predictable effects, but due to the fact that strains aren’t grown openly in fields (a.k.a. open pollinated, or OP), they might have more distinct strain profiles than landrace strains from Africa or the Middle East. One of the ways to guess what the effects of a landrace Thai strain will be is to figure out whether it’s a highland or lowland variety, but it’s not foolproof.

In general, it’s said that highland varieties from Southeast Asia represent a more pure sativa lineage, and the lowland strains represent more hybridized effects. It’s certainly true that the differences in climate come into play, but in this case, it may be more about politics and law enforcement. The earlier pure sativas may have actually come from the tropical lowlands and been moved into the mountains, and then later on, highly organized traffickers moved into the lowland farms with strains that were hybridized for yield and shorter flowering times.

Keeping that in mind, let’s go over some Thai landrace genetics that you should know about!

Can I find Thai landrace strains on today’s market?

Although some of the treasures from yesteryear may be long gone, there’s a lot still out there, especially in private collections. When it comes to retail stores, you might find strains with 'Thai' in the name but they don't usually represent the vintage stuff all that closely. The only commercial producer we know of that has a line up of authentic landrace strains is Washington State's Kiona. You can see their heirloom Vietnam Black aka VB 164 below, which is fairly close match to some vintage Thai strains.

Other than being able to shop for Kiona products, we've found it really hard to locate products like this, so the best option might be to look for home growers that might share with you! Here's some of the old favorites and modern iterations that are still passed around today:

Purple Thai

Veteran landrace breeders Snowhigh and Coastal collaborated on Jedi Mind Trip Colombian but this cross of Oaxacan and Thai landrace sativas is also available from Kyle Kushman at Homegrown Cannabis Company. If autoflowers are your best option, Ethos now offers their own autoflowering Purple Thai.

Chocolate Thai

Vintage Chocolate Thai seeds are harder to come by, but DC Seed Exchange has a pack of Cocoa Puffs by Hazeman in stock. Top Dawg Seeds has a Chocolate Thai cross called Chocolate Thunder available at The Seed Source.

Pineapple Thai

For a taste of Thailand in a short-flowering package, check out 707 Seedbank’s Pineapple Thai from Breeder’s Direct. Keep in mind that most enthusiasts feel like landrace sativas bred into shorter flowering times lose much of the energy and mystique that makes them distinct!

Lemon Thai

Although this delicious strain was found growing in Hawaii, it’s said to be a cross of Hawaiian and Thai landraces. This heirloom strain is a parent of OG Kush and you can find it at Heritage Seed Co. It’s not often that such an absolute legend becomes available in seed form, especially as an F4! Another heirloom option is Pablo’s Lemon Thai, which crosses Lemon Thai with Colombian and other premium genetics, but this one comes at a premium price..

Non-domesticated

If you’re brave (and skilled) enough to try domesticating your own Thai strain, you can look for imported seeds harvested from plants actually growing in Thailand. The Real Seed Company’s landrace and Southeast Asian varieties including this gorgeous Highland Thai. Curious but less adventurous growers can look into semi-domesticated options like something from ACE Seeds, or this Destroyer (fem available) from CannaBioGen that are meant to capture authentic Thai traits into more practical form.